The FDA Wants to Know: Is Your Software Still Supported?

Feb 14, 2026

Interlynk

Why Component Support Status Is the Hardest Part of Medical Device SBOMs

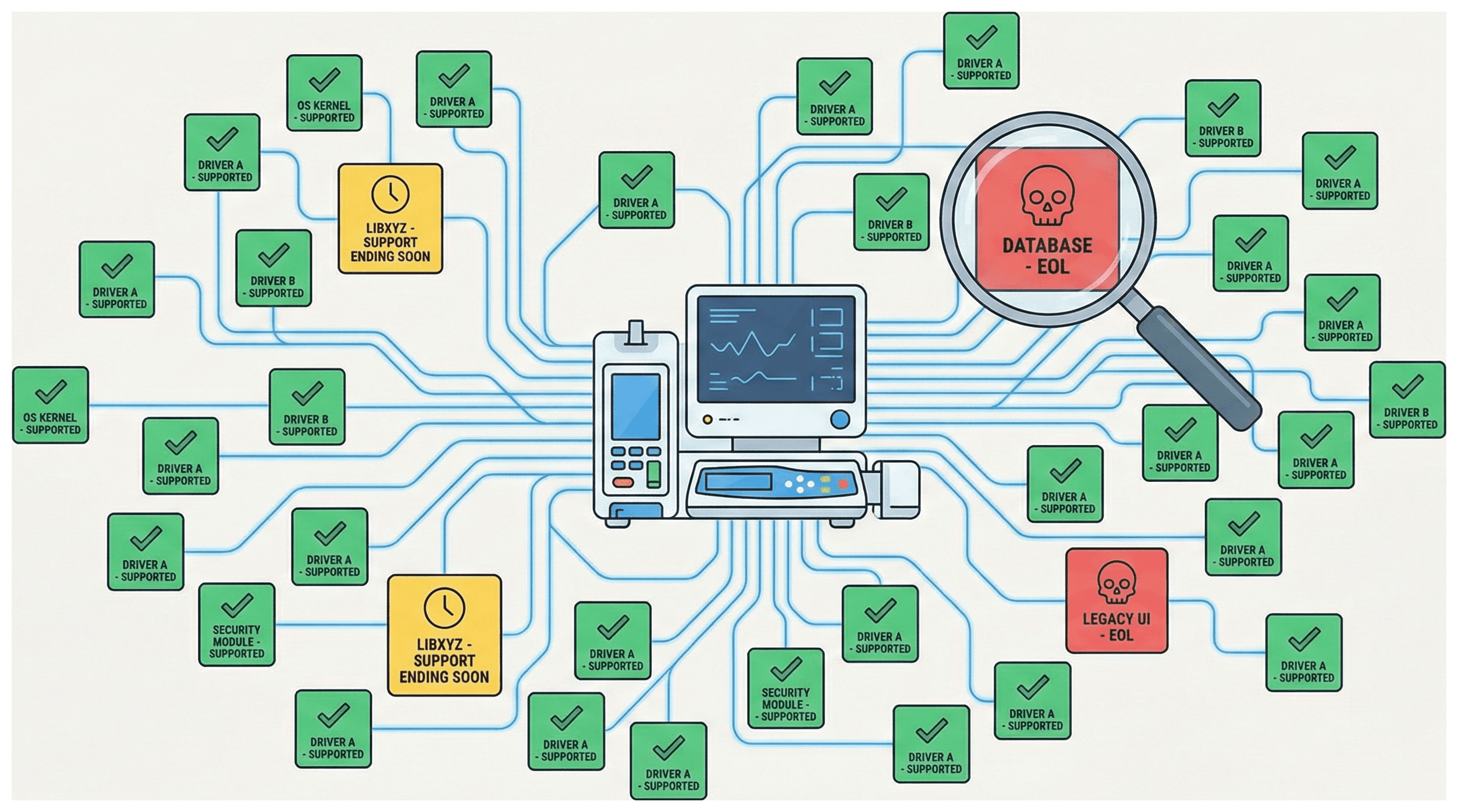

If you're a medical device manufacturer preparing a premarket cybersecurity submission, you've likely heard that the FDA now requires a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM). What you may not realize is that the SBOM itself is just the beginning. Since October 2023, the FDA has been actively enforcing requirements that go far beyond listing the software components in your device. They want to know whether those components are still being taken care of.

This article breaks down what the FDA actually requires for component support status, why it's surprisingly difficult to get right, and what practical approaches exist today.

What Exactly Does the FDA Want?

For every component in your SBOM — whether it's a commercial library, an open-source package, or a piece of off-the-shelf software — the FDA expects two specific pieces of information:

1. Level of Support

Is this component actively maintained? Has the maintainer stopped working on it? Has it been abandoned entirely? The FDA cares because an unsupported component is a ticking clock. When a vulnerability is discovered in a library that no one is patching, your device inherits that risk with no clear path to remediation.

The FDA generally recognizes these categories:

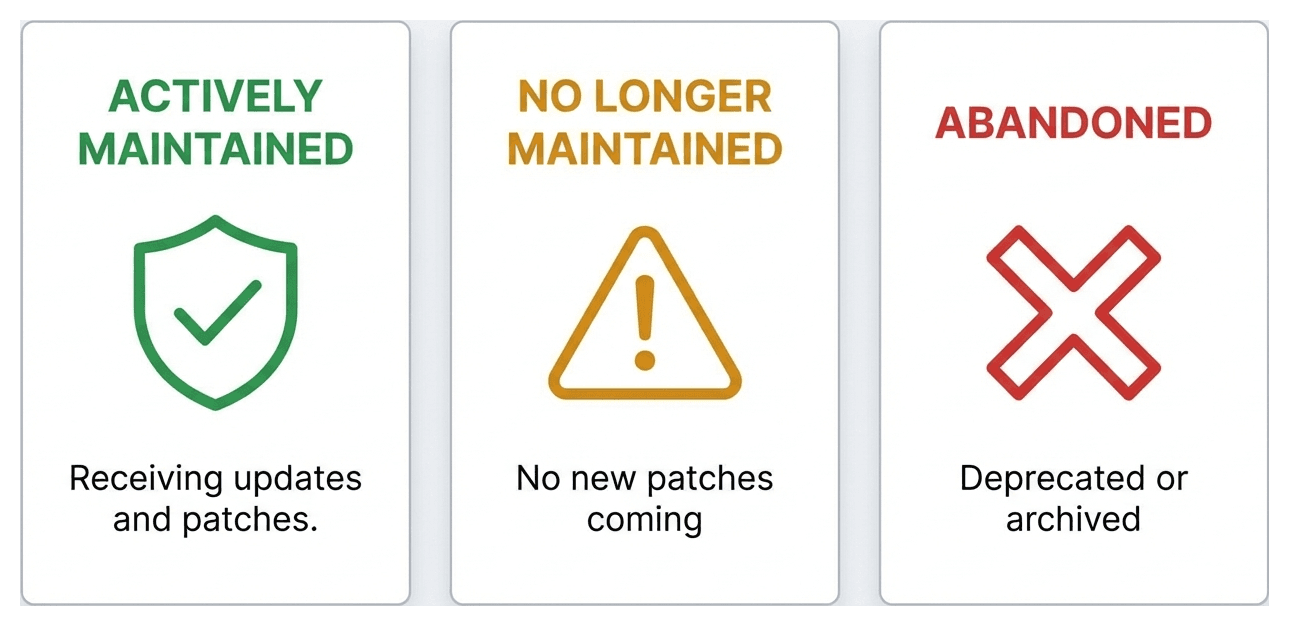

Actively Maintained — Someone is watching the code, issuing updates, and patching security issues.

No Longer Maintained — The component existed in a maintained state at some point, but the maintainer has moved on. No new security patches are coming.

Abandoned — The project has been explicitly deprecated, archived, or left without any maintainer activity for an extended period.

2. End-of-Support / End-of-Life (EOS/EOL) Date

This is the date when support for the component will end — or has already ended. For proprietary components, this might come from a vendor support contract. For open-source components, this is where things get complicated (more on that shortly).

If you can't provide support information for a particular component, the FDA expects a written justification explaining why. "We didn't know" is not an acceptable answer.

This information is submitted alongside vulnerability assessments and remediation plans as part of the broader cybersecurity risk report. Submissions that lack adequate SBOM and component support data may be refused — the FDA has made this clear.

Why Is This So Hard?

On paper, this sounds straightforward: look up each component, check if it's supported, write down the date. In practice, this turns out to be much harder than it sounds. Here's why.

The SBOM Format Gap

The two dominant SBOM standards — SPDX and CycloneDX — were not designed with FDA support status requirements in mind.

SPDX (maintained by the Linux Foundation) has no native fields for component support level or end-of-support dates. There is simply no place in the standard SPDX schema to express "this component is no longer maintained" or "support ends on 2025-06-30." You can use SPDX's annotation mechanism or external document references, but these are workarounds — not structured, machine-readable fields that tooling can consume consistently.

CycloneDX is slightly better positioned. It supports a flexible properties extension mechanism where you can attach arbitrary key-value pairs to components. This is how platforms like Interlynk handle support status today — by writing custom properties like:

But here's the catch: these are vendor-specific extensions, not part of the core CycloneDX specification. Another tool reading this SBOM would have no idea what interlynk:component:support_level means unless it was specifically built to understand it. There is no universal, standardized way to express support status in either format.

This means that organizations often resort to exporting support data as a separate CSV file alongside the SBOM, creating a fragmented picture that requires manual reconciliation. It's functional, but it's fragile.

The Open-Source Inference Problem

For commercial software, determining support status is relatively straightforward. You have a vendor. You have a support contract. The contract has an expiration date. Done.

Open source is a different world entirely.

Most open-source projects don't publish formal support timelines. There's no "End of Support" page for the thousands of transitive dependencies in a typical software project. The FDA acknowledges this challenge, but still expects manufacturers to provide the information — or justify why they can't.

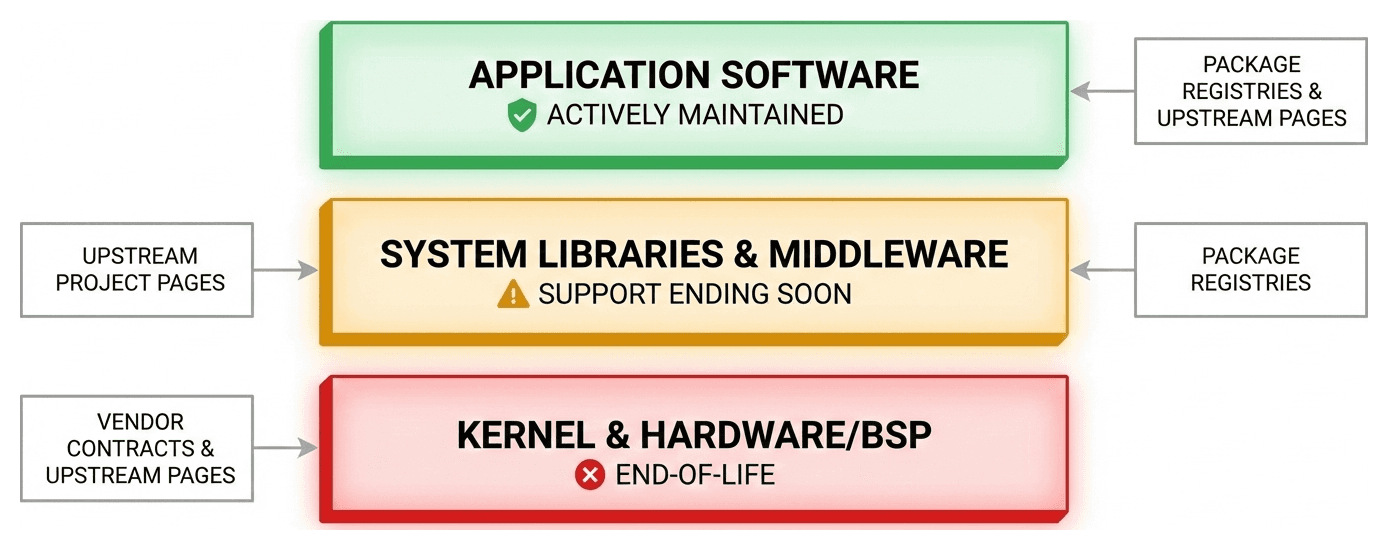

So how do you determine the support status of an open-source component? You infer it. And inference requires data from multiple sources:

Package Registry Activity — When was the last version published on npm, PyPI, Maven Central, RubyGems, or whichever registry the package lives on? If the latest version was released within the last year, that's a strong signal of active maintenance. If nothing has been published in three years, that's a red flag.

Source Repository Activity — When was the last commit to the project's GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket repository? Is the repository archived? Has it been explicitly marked as deprecated?

Known EOL Databases — Projects like endoflife.date (xeol.io) maintain structured data about end-of-life dates for well-known software products. These cover major frameworks, languages, and operating systems — but they represent a fraction of the total ecosystem.

Package Deprecation Flags — Some registries support explicit deprecation markers. npm allows maintainers to deprecate packages. PyPI packages can be yanked. But adoption of these mechanisms is inconsistent across ecosystems.

The problem is that no single source gives you the complete picture. A package might show no new registry releases in two years — but the maintainer is actively committing, just hasn't cut a release. Or a repository might show recent activity, but it's all automated dependency bumps — not meaningful maintenance.

Determining support status requires correlating signals across multiple sources and applying judgment. It's detective work, not a database lookup.

The Scale of Ecosystems

A modern medical device doesn't just use a handful of libraries. A typical firmware or application stack might pull in hundreds or even thousands of dependencies across JavaScript, Python, Java, .NET, Rust, Go, C/C++, and more — each with millions of available packages and each with different conventions for how lifecycle information is communicated.

Some ecosystems let maintainers explicitly deprecate a package. Others have no deprecation mechanism at all. C and C++ libraries often have no package manager presence whatsoever — they're downloaded as source archives or compiled directly into the build. There is no universal API you can call to ask "is this component still supported?" across all of them.

This means that providing consistent support status across your entire SBOM requires ecosystem-specific knowledge and data pipelines — a significant infrastructure challenge.

The Embedded and Custom Build Problem

Medical devices frequently run on custom Linux builds created with build systems like Buildroot or Yocto/OpenEmbedded. Unlike typical software that installs pre-built packages, these systems compile an entire operating system — kernel, system libraries, utilities — from source code.

This adds layers of complexity to support status:

The upstream vs. vendor fork question — In embedded systems, support status often depends not just on the upstream project, but on vendor-modified forks and long-term contracts. A device might use the Linux 5.15 kernel, which has a known upstream EOL date — but the version actually running on the device is a vendor-patched fork. Whether that fork is maintained depends on the vendor, not the open-source project.

Hundreds of components outside traditional registries — Embedded build systems pull source code for hundreds of packages (OpenSSL, busybox, systemd, etc.) and compile them for the target hardware. Many of these don't exist in package registries like npm or PyPI, so the usual automated checks simply don't apply. Each one must be traced back to its upstream project manually.

Proprietary hardware components — Board Support Packages from chip vendors (NXP, TI, Qualcomm, etc.) include proprietary drivers and firmware with support lifecycles tied to the vendor's product roadmap. The only way to know the EOL date is to check your vendor agreement.

For these embedded scenarios, determining support status is often a manual research exercise — and one of the most time-consuming parts of an FDA submission.

A Practical Framework for Getting This Right

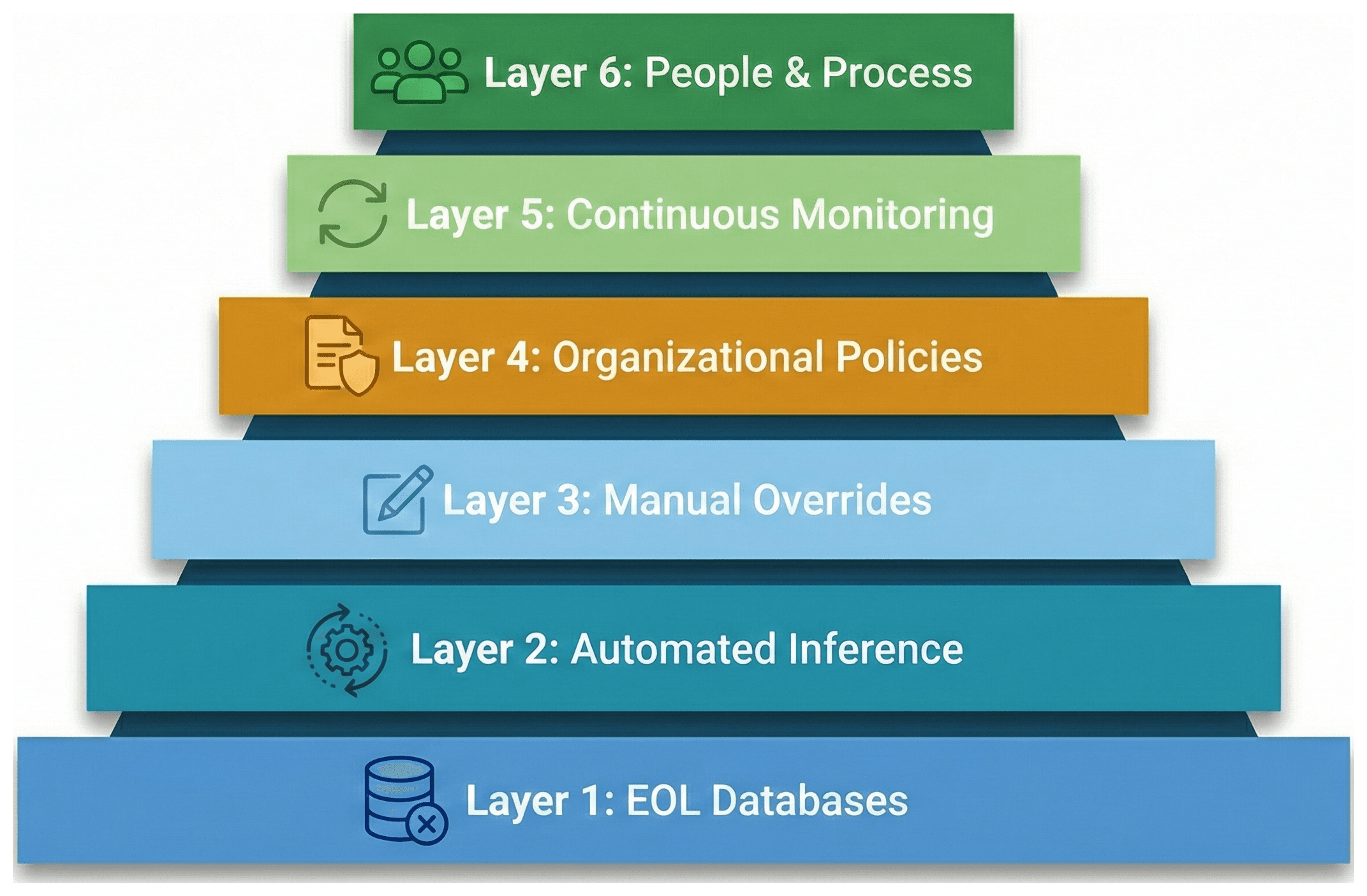

Given all this complexity, what should a medical device manufacturer actually do? Here is a layered approach that builds from automated foundations to human oversight.

Layer 1: Leverage Known EOL Databases

Start with what's already documented. Databases like endoflife.date provide structured EOL/EOS data for hundreds of well-known products — programming languages, frameworks, operating systems, databases, and more. This won't cover your entire SBOM, but it will handle the "big rocks" — the major components that represent the most risk.

For components with known EOL dates, the mapping is straightforward: if EOL has passed, the component is no longer maintained. If EOS has passed, support has ended. If the product is deprecated, treat it as abandoned.

Layer 2: Automate Inference from Package and Repository Metadata

For the long tail of open-source components without formal EOL data, set up automated checks:

Package freshness: Query the relevant package registry. If the latest version was published within a configurable threshold (commonly 365 days), classify as actively maintained.

Repository activity: Check the source repository's last commit date. If commits are recent, that's a positive signal.

Deprecation flags: Check whether the package or repository has been explicitly deprecated or archived.

Combine these signals with sensible defaults: if both the registry and repository show no activity beyond your threshold, classify as no longer maintained. If the repository is archived or the package is deprecated, classify as abandoned.

This automated approach won't be perfect — some active projects simply release infrequently — but it provides a defensible baseline that covers the bulk of your SBOM.

Layer 3: Manual Overrides with Audit Trails

Automation will get you 70-80% of the way there. The rest requires human judgment. Your team needs the ability to:

Override automated classifications — A security engineer might know that a seemingly inactive project is actually maintained by an internal team or a commercial vendor under contract.

Set explicit EOL dates — For proprietary components or vendor-supported libraries, manually enter the contract expiration date.

Document justifications — When support status genuinely cannot be determined, record why. "Component XYZ is a vendored C library with no public repository or registry presence. The original author is unresponsive. We have classified it as unspecified and included it in our risk assessment" is a legitimate justification.

These overrides should be tracked with full audit trails — who changed what, when, and why — because the FDA may ask.

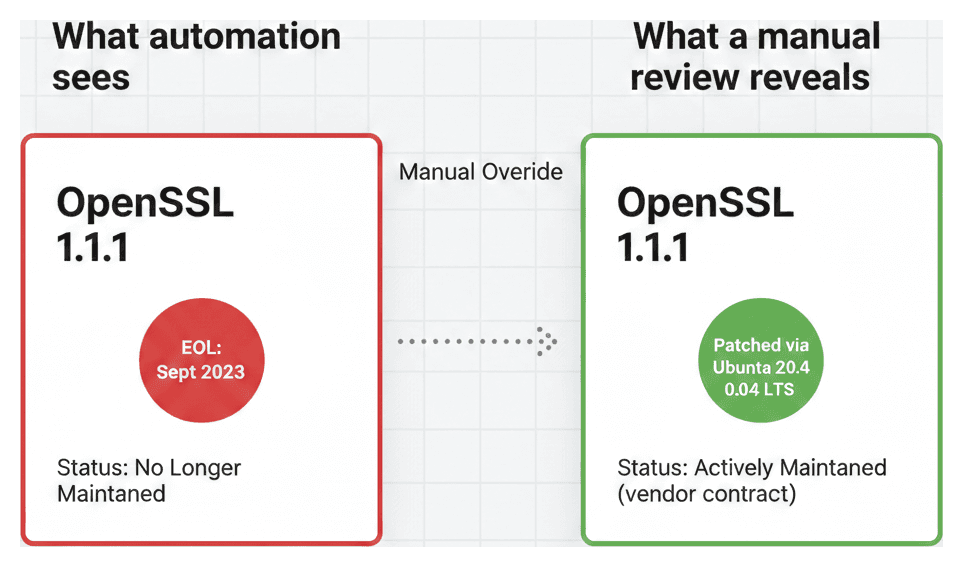

A real-world example: the OpenSSL problem

Consider a medical device that uses OpenSSL 1.1.1 — one of the most widely deployed cryptographic libraries in the world. Upstream, OpenSSL 1.1.1 reached its official End-of-Life on September 11, 2023. An automated system would correctly flag this and classify the component as "No Longer Maintained." Case closed?

Not necessarily. If the device runs on Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, Canonical backports security fixes for OpenSSL 1.1.1 as part of their long-term support commitment. The upstream project is end-of-life, but the specific build your device uses is still receiving patches through your distribution vendor.

This is a distinction that automation alone cannot make. The automated layer flags the risk. The manual override captures the nuance:

> "OpenSSL 1.1.1 upstream is EOL, but our device uses the Ubuntu 20.04 LTS-maintained build. Canonical provides security patches under our support contract through April 2025. EOL date set to contract expiration."

That override — documented with a justification and tied to a specific support contract — is exactly the kind of evidence the FDA expects.

Now multiply this across every component in a complex device, and the need for a structured override system with audit trails becomes obvious.

Layer 4: Organizational Policies

Different organizations may need different thresholds and rules. A component that's been dormant for six months might be acceptable in one context but concerning in another. Organizations should be able to:

Configure the activity thresholds used for automatic classification

Set organization-wide overrides for components they've independently verified

Define policies that flag components with certain support statuses for review

Layer 5: Continuous Monitoring

Support status is not a point-in-time assessment. A component that was actively maintained when you submitted your premarket application could become abandoned six months later. Continuous monitoring — recalculating support status on a regular cadence and alerting when components transition to concerning states — is essential for maintaining your cybersecurity risk posture throughout the device lifecycle.

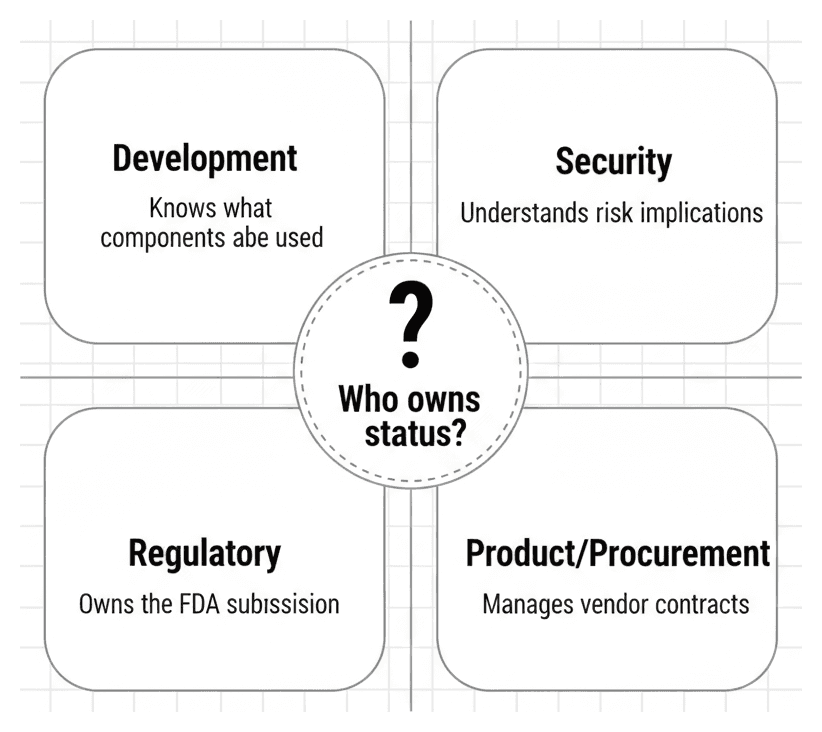

Layer 6: People and Process

Technology and data are only part of the equation. One of the most underestimated challenges is the organizational one: who actually owns this work?

In most medical device companies, the answer is unclear — and that's the problem.

Development builds the software and chooses the components — but moves on to the next release. Tracking lifecycle status across hundreds of dependencies isn't part of their daily workflow.

Security understands the risk of unsupported components — but often lacks the context of why a specific version was chosen or whether an internal fork is being maintained.

Regulatory owns the FDA submission — but depends entirely on engineering to provide the data. They can't determine whether busybox 1.35.0 in a Yocto build is still receiving patches.

Product/Procurement manages the vendor contracts that determine EOL dates — but may not connect a contract renewal to the cybersecurity risk profile of a device already on the market.

No single person has the complete picture. The firmware engineer knows the kernel fork is maintained. Procurement knows the BSP support contract expires next year. The open-source program office tracks community health for key dependencies.

The organizations that handle this well establish clear, cross-functional ownership — defining who reviews support status classifications, who monitors for changes, and who updates records when a vendor contract is renewed or a component is replaced. Without this process clarity, even the best tooling produces incomplete results. The hardest data to capture is the institutional knowledge that lives in people's heads, not in package registries.

What Needs to Change

The current state of affairs is workable but far from ideal. Several things would help:

SBOM standards need native support status fields. Both SPDX and CycloneDX should include standardized, machine-readable fields for support level and EOL/EOS dates. Vendor-specific properties and CSV side-channels are not sustainable. The FDA's requirements are clear — the standards should reflect them.

Package registries need better lifecycle metadata. If npm, PyPI, and Maven Central exposed structured EOL and support status information alongside version data, the entire ecosystem would benefit. Some registries are moving in this direction, but adoption is uneven.

The embedded ecosystem needs better tooling. Buildroot and Yocto generate detailed manifests of what they build, but mapping those manifests to upstream support status is largely a manual process. Better integration between embedded build systems and SBOM/support-status tooling would significantly reduce the burden on device manufacturers.

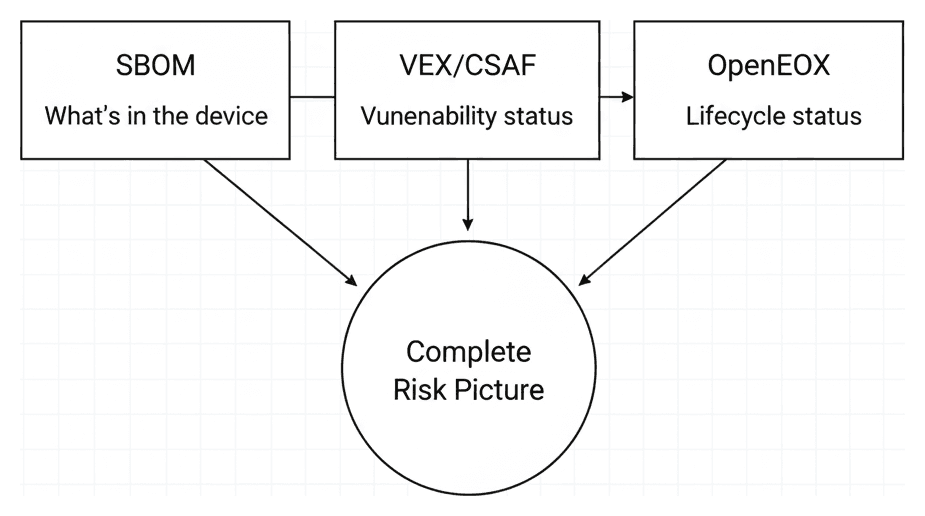

Industry collaboration on EOL data — and OpenEoX is leading the way. Community projects like endoflife.date have started cataloging EOL dates for popular products, but what's been missing is an industry-backed standard for how lifecycle data should be structured and exchanged. That's exactly what OpenEoX aims to provide.

Launched in December 2023 as an OASIS Technical Committee, OpenEoX is backed by Cisco, Dell, Microsoft, Red Hat, Qualys, and others — with CISA contributing as well. The standard defines clear lifecycle phases that map directly to what the FDA is asking for:

End-of-Sales — vendor stops accepting new orders

End-of-Security-Support — security patches stop being issued (the critical one for medical devices)

End-of-Life — full retirement, no further support of any kind

The key insight behind OpenEoX is that it doesn't replace existing standards — it fills the gap between them. Your SBOM tells you what's in your device. VEX and CSAF tell you what vulnerabilities apply. OpenEoX adds the missing piece: how long each component will be supported.

The specification is still in active development (v1.0 is in progress), but the direction is clear and the industry backing is substantial. For medical device manufacturers, OpenEoX is worth watching closely. It won't solve today's submission deadline, but it represents where the industry is heading — toward a universal, machine-readable format for lifecycle data that any tool can produce and consume.

The Bottom Line

The FDA's support status requirements exist for a good reason: unsupported software in medical devices is a patient safety issue. But meeting these requirements is genuinely difficult — not because manufacturers aren't willing, but because the data infrastructure doesn't fully exist yet.

The path forward involves a combination of automated inference, curated databases, manual oversight, and — critically — better tooling.

At Interlynk, we've built infrastructure specifically to address this gap — combining automated support level inference across package registries and source repositories, curated EOL databases, manual override workflows with expiration controls, and full audit trails designed for FDA scrutiny. Every layer of the framework described in this article reflects real challenges we've solved for medical device manufacturers navigating premarket submissions.

If you're struggling with support status data, you're not alone. The challenge is real — but it's solvable, and the tooling is maturing fast.

Interlynk provides SBOM management and software supply chain security tools purpose-built for regulated industries. To learn more about how we handle FDA support status requirements, visit interlynk.io.